Push Ups: Benefits, Muscles Worked, and More

Programming the Push-Up

In training programming, push-ups are meant to be performed for high volume sets in a manner that leverages the lifter’s own weight against their musculature.

For the majority of lifters, this is gauged by their own rate of perceived exertion (RPE), and as such will vary between each individual case.

If the push-up is being utilized as a primary compound movement, a 8-9 on the RPE scale is sufficient - otherwise, for accessory compound usage, somewhere between 6-8 is better.

Because of the fact that most push-up performers cannot alter their own bodyweight at short notice, advanced methods of programming the push-up will involve the usage of repetition schemes (or exercise substitution) in order to achieve the right level of training intensity.

Who Should Do Push-Ups?

Push-ups are quite simple in terms of exercise mechanics, but may be difficult to perform for individuals entirely new to resistance training, as they may not have the prerequisite upper body strength to perform the movement correctly; In this case, novice exercisers will wish to perform knee-ups instead.

Otherwise, push-ups are an excellent movement for practically all types of exercisers - especially athletes and other types of lifters in need of upper body muscular endurance and power.

How to do Push-Ups

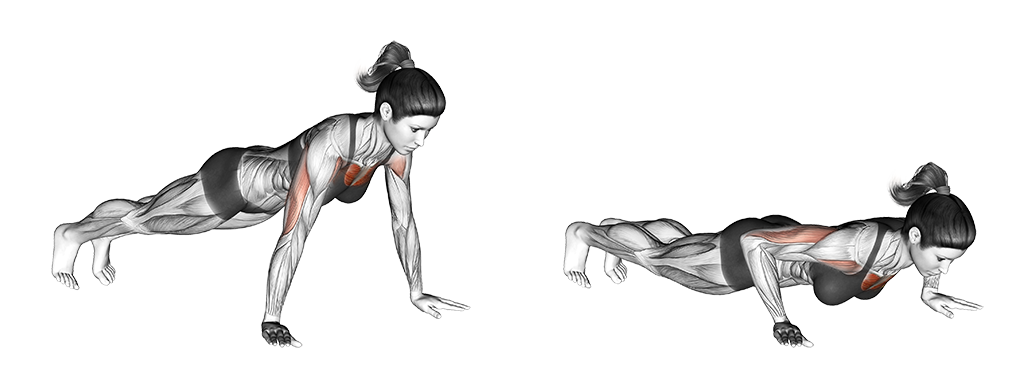

In order to perform a repetition of the push-up, the lifter will enter a plank stance on the floor with their toes touching the ground and their palms set parallel to the shoulders.

The legs should remain fully extended throughout the set, with the core firmly contracted and the glutes engaged so as to maintain a straight torso.

Keeping the neck neutrally aligned with the spine, the exerciser will bend at the elbows and slowly lower their chest towards the ground, ensuring that their torso is rigid and their shoulders are not rotating internally as they do so.

Once the chest is within several inches of touching the ground, the exerciser will push through the palms of their hands and slowly raise their torso back to the starting position. As they do so, the elbows will naturally extend and the pectoral muscles will contract.

Once the arms are nearly fully extended, the repetition is considered complete.

What Muscles Do Push-Ups Work?

Push-ups are the very definition of a compound exercise, and as such train more than a single muscle group at a time - although not all to the same extent.

The muscles trained to the greatest extent by push-ups are referred to as primary mover muscles, whereas muscles trained to a lesser (but still dynamic) capacity are called the secondary mover muscles.

Other muscle groups that solely contract isometrically are referred to as stabilizers.

Primary Mover Muscles

With each repetition of the push-up, it is the muscles of the triceps brachii, pectorals and the anterior head of the deltoids that are recruited to the greatest extent.

For the most part, the triceps and pectoral muscles will bear the majority of the body’s weight, making the push-up particularly effective at training said muscles.

Secondary Mover Muscles and Stabilizer Muscles

In terms of secondary mover muscles, push-ups will primarily work the serratus anterior and the medial head of the deltoids - whereas the core musculature, glutes and forearms are used as stabilizing muscles throughout the entire movement.

What are the Benefits of Doing Push-Ups?

All forms of resistance exercise come with a shared set of benefits - but when specifically performing push-ups, there are quite a number of positive effects relating to upper body muscular function and size.

When combining push-ups with a proper diet and sufficient recovery, these benefits may be fully realized by the exercise, many of which are the very reason for the push-ups popularity in the first place.

Muscular Size and Strength Developments in the Upper Body

The clearest and most sought-after benefit of performing push-ups is its ability to cause hypertrophy in the muscles of the upper body.

The pectoralis muscle group, the deltoids and the triceps all receive intense training stimulus when push-ups are performed, resulting in subsequent hypertrophy and strength adaptations, as is characteristic of all resistance training exercises.

Unlike other resistance exercises, however, push-ups achieve this primarily through high volume sets, rather than with a significant amount of weight - therein favoring hypertrophy to a greater extent as well.

Highly Accessible and Easily Adjustable

Much like other novice-level calisthenic exercises, the push-up is both easy to perform and easy to adjust so as to meet any training needs that may be present.

Such accessibility is a result of the low-impact nature of the push-up, as well as its relatively simple mechanics, requiring no advanced exercise familiarity or above-average conditioning to perform.

While this is not to say that the push-up is free of injury risk, it is nonetheless an excellent starting movement that can easily be scaled as the exerciser becomes more advanced in terms of training experience and physical conditioning.

Improved Core Strength and Stability

One often overlooked benefit of regular push-up performance is its capacity to strengthen the muscles of the core - primarily those of the abdominals, of which keep the torso rigid and stable throughout each set.

The push-ups ability to improve core strength is on account of the plank stance with which it is performed.

Apart from performing the exercise on the hands rather than the elbows, the plank and the push-up are practically identical in terms of isometric core muscle contraction, and as such will share much the same abdominal muscle benefits as well.

Carryover to Other Push Exercises

The push-up is the quintessential “push” exercise - a denomination of resistance exercises characterized by their adductive production of force and involvement of muscle groups like the pectorals, deltoids and triceps.

Regularly performing push-ups can indirectly improve the exerciser’s performance in seemingly unrelated movements like the bench press, overhead press or chest fly.

The push-up’s capacity to produce carryover to other exercises is caused by both its muscular development and the fact that it helps reinforce mechanics like elbow extension and shoulder adduction, of which are featured in many of the aforementioned beneficiary exercises.

Athletic Applicability and Upper Body Explosiveness

The push-up is considered a classic athletic training exercise for a reason; the training stimulus produced with high volume push-up sets easily results in improved muscular rate of force development, or what is otherwise known as muscular power and explosiveness.

When combined with other athletically beneficial exercises like sprints and plyometrics, the push-up can contribute greatly to building a well-rounded athletic training program perfect for football, calisthenics and martial art athletes.

Most Common Mistakes Made When Doing Push-Ups

Despite the relatively simple form of the push-up, there are nonetheless several frequently made mistakes that should be corrected so as to create a safer and more effective exercise.

Allowing the Torso to Collapse

Throughout each repetition of the push-up, the exerciser must ensure that their torso is held firmly straight and stable through proper contraction of the core and gluteal muscles. Allowing the torso to collapse at the waist or chest will greatly increase the amount of pressure placed on the joints of the upper body, and effectively reduce the range of motion of the exercise.

Both instances result in a more dangerous and less effective push-up, and as such it is important to brace the core and squeeze the glutes throughout the push-up’s range of motion.

Locking Out the Elbows

One mistake even advanced exercisers make is locking out the elbows at the end of each push-up repetition.

When the arms are held in a state of full extension, far more weight and tension is placed on the elbow joint than is necessary - potentially resulting in irritation and injury, especially for high volume push-up sets.

In order to avoid excessive wear and tear on the elbows, the exerciser should instead almost lock their elbows out. Ensuring that the arms do not enter a state of full extension will distribute the push-up’s resistance more evenly throughout the arms and help prevent overuse injuries of the elbow.

Improper Hand Placement

In order to reduce strain on the wrist and shoulders, the conventional push-up should have the hands parallel to the shoulders along a lateral plane, as if forming a letter “T” with the upper body.

This does not mean that the hands should be below the shoulders, however, and a palm placement slightly further apart than shoulder-width will help distribute force through the arms in a less dangerous manner.

Arching the Chest or Head Downwards

Exercisers struggling to perform the push-up may find themselves arching their upper torso towards the ground - either as a result of their core musculature giving out or because they are subconsciously “cheating” the repetition by reducing their range of motion.

In either case, doing so will take much of the resistance away from the chest and shoulders, potentially negating the benefits of the exercise.

It is best to perform push-ups with the torso relatively straight throughout the repetition, with the chest parallel to the waist and the lower back at a neutral curvature.

Push-Up Variations

Incase push-ups aren’t up to standard, there are several variations that can help meet any lifter’s training needs - be it less resistance, a greater focus on the triceps or an increase in actual difficulty.

1. Knee-Ups

For novice exercisers who can’t perform a full set of push-ups, they may pad out their training volume with knee-ups instead.

Knee-ups are simply conventional push-ups performed with the exerciser on their hands and knees, rather than their feet.

This effectively reduces how much of the body’s own weight is leveraged against the muscles of the upper body, and can allow those without sufficient body strength to train said muscles without the need for a full set of push-ups.

2. Decline Push-Ups

On the other hand, exercisers who have surpassed the push-up in terms of training effectiveness will find that performing the movement with their feet elevated higher than their head allows for progressive overload to continue.

This variation is known as a decline push-up, and is considered to be a progression step from the conventional push-up for exercisers that wish to increase the amount of resistance placed on their shoulders and triceps.

3. Narrow Grip Push-Ups

For exercisers who find that their triceps are lagging behind, substituting the conventional push-up with its narrow grip counterpart can help place more volume therein.

In all other aspects, the close grip push-up is identical to its conventional counterpart - with the sole difference being that the hands are placed lower and closer together, thereby shifting the emphasis of the movement from the chest and shoulders to the triceps.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Do Push-Ups Burn Fat?

Yes - but not effectively.

Push-ups are an anaerobic exercise and will not burn as many calories as aerobic exercises like jogging or swimming.

How Often Should You Do Push-Ups?

In order to avoid overtraining and injury, you should only perform push-ups 3-4 times a week, with at least one day of rest in between workout sessions.

Resistance exercises like push-ups produce small tears in the skeletal musculature of the body - tears that require time in order to recover from. Performing push-ups every day or at a very high level of intensity without rest can easily cause the body to become overwhelmed.

What are Push-Ups Good for?

Push-ups are highly versatile, and are used for purposes ranging from building up muscle mass in the chest to technical sports-specific carryover. In order to get the most out of a set of push-ups, it is important to program them correctly and to switch to a more niche variation if needed.

References:

1. Hassan, S. (2018). The Effects of Push-Up Training on Muscular Strength and Muscular Endurance. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 8(11), 660–665.

2. Hewit, Jennifer & Jaffe, Daniel & Bedard, Alexander. (2018). Teaching the Proper Push-up Position: Editor: Ferman Konukman. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance. 89. 50-52. 10.1080/07303084.2018.1491765.